Bloodstain patterns can be pivotal evidence

Although admissible in court for more than 150 years, the validity of bloodstain pattern analysis has recently been questioned. In 2009, a National Research Council report called for more objective methods in forensic science

In forensic science, researchers use black box studies to measure the reliability of methods that rely mainly on human judgment instead of techniques that depend on laboratory instruments.

Researcher Austin Hicklin and his colleagues at Noblis, a not-for-profit research institute, set out, with funding from NIJ, to assess the validity of bloodstain pattern analysis by measuring the accuracyIn scientific and measurement contexts, "accuracy" refers to the degree of proximity or closeness between a measured value and the true or actual value of the measured quantity. Accuracy indicates how well a measurement reflects Read Full Definition of conclusions made by actively practicing analysts. In what is now the largest study of its kind, they applied their extensive experience executing “black box” studies of fingerprint, handwriting, and forensic footwear examination to bloodstain pattern analysis.

Contradictory Conclusions and Corroboration of Errors

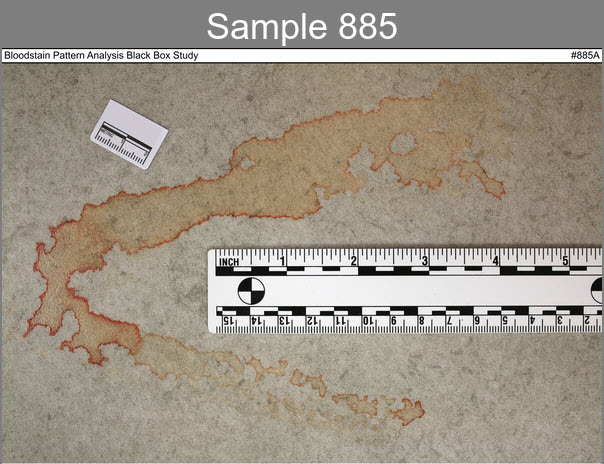

The Noblis researchers recruited 75 practicing bloodstain pattern analysts to examine 150 distinct bloodstain patterns (see Figure 1) over four months. The study included 192 bloodstain images that were collected in controlled laboratory settings as well as operational casework. The researchers planned to measure the overall accuracy, reproducibility, and consensus of the group and compare performance between participants by their background and training.

Unlike previous black box studies performed by Noblis, bloodstain pattern analysis did not have well-established conclusion standards used throughout the community, so the researchers had to establish a set of conclusions for the participants to use. They developed three complementary approaches to collect participants’ assessments: summary conclusions (dubbed “tweets”), classifications, and open-ended questions. Each participant received requests for a mix of the three types of responses.

The researchers found that 11% of the time, the analysts’ conclusions did not match the known cause of the bloodstain. Although the consensus, or average group response, was generally correct (responses with a 95% supermajority were always accurate), the rate at which any two analysts’ conclusions contradicted each other was not negligible, at about 8%. Focusing specifically on the incorrect responses, the researchers found that those same errors were corroborated by a second analystA designated person who examines and analyzes seized drugs or related materials, or directs such examinations to be done; independently has access to unsealed evidence in order to remove samples from the evidentiary material for Read Full Definition 18% to 34% of the time. The error rates measured in this work are consistent with previous studies. Participants’ backgrounds or training were not associated with performance.

Because the conclusions reached by participants were sometimes erroneous or contradicted other analysts, this suggests potentially severe consequences for casework — especially regarding the possibility of conflicting testimony in court. Moreover, in the absence of widely accepted criteria for conclusion classifications, one cannot, the researchers argue, expect high rates of reproducibility among analysts.

Importantly, disagreements among analysts were often the result of semantics. This lack of agreement on the meaning and usage of bloodstain pattern terminology and classifications underscores the need for improved consensus standards. Experts on the study team also felt that many conclusions expressed an excessive certainty given the sparsely provided available data Information in analog or digital form that can be transmitted or processed. Read Full Definition.

Information in analog or digital form that can be transmitted or processed. Read Full Definition.

Caution Against Generalizing to Operational Error Rates

The Noblis study differed from operational casework in that the analysts were asked to respond based solely on photographs and were not provided additional case-relevant facts that may have influenced their assessments. Moreover, the means of reporting conclusions differed from how bloodstain pattern analysts typically say their conclusions.

Given these notable differences, Hicklin and his team caution that the results should not be taken as precise"Precise" refers to the degree of closeness or consistency between multiple measurements or values taken under the same conditions. It indicates how well these measurements agree with each other, regardless of whether they are accurate Read Full Definition measures of operational error rates; the error rates reported describe the proportion of erroneous results for this particular set of images with these particular patterns. It should not be assumed that these rates apply to all bloodstain pattern analysts across all casework. Rather, the work provides quantitative estimates that may aid decision-making, process and training improvements, and future research.

National Institute of Justice, “Study Assesses the Accuracy and Reproducibility of Bloodstain Pattern Analysis,” December 14, 2022, nij.ojp.gov:

https://nij.ojp.gov/topics/articles/study-assesses-accuracy-and-reproducibility-bloodstain-pattern-analysis