Sexual Dimorphism: Reading Sex from the Human Skeleton

Sexual dimorphism refers to the observable physical differences between males and females of the same species, beyond their reproductive organs. In forensic science, particularly forensic anthropology, it’s the cornerstone principle that allows investigators to estimate the sex of an unknown individual from their skeletal remains. These differences, driven by genetics and hormones, manifest in the size and shape (morphology) of the bones, providing crucial clues for building a biological profile and, ultimately, identifying the person.

The Biological Basis

The differences we see in the adult human skeleton are largely the result of hormonal processes that begin during puberty. While both sexes have the same 206 bones, the influence of testosterone in males and estrogen in females dictates their final size and shape.

Generally, testosterone promotes more robust bone growth, leading to larger, stronger bones and more pronounced muscle attachment sites. This is why the male skeleton is, on average, larger and more rugged than the female skeleton. Conversely, estrogen influences the female pelvis to widen in preparation for potential childbirth. These developmental pathways result in a spectrum of traits, but they follow predictable patterns that forensic anthropologists are trained to recognize. It’s crucial to understand that these are population-level differences, and an individual may exhibit a mix of traits. Therefore, anthropologists assess multiple indicators across the skeleton to make a determination.

Forensic Significance

Estimating sex is one of the first and most critical steps in creating a biological profile from skeletal remains. It immediately narrows the search for a missing person by roughly 50%. Forensic anthropologists use their deep knowledge of sexual dimorphism to make this assessment, with a focus on the two most reliable bones: the pelvis and the skull.

- The Pelvis: This is the single most accurate indicator of sex. The female pelvis is shaped by the functional demand of childbirth, making it wider and more rounded. Key indicators include:

- Ventral Arc: A distinct ridge of bone on the anterior surface of the pubic bone, present only in females.

- Subpubic Angle: The angle formed by the pubic bones is wide and U-shaped in females (typically > 90°), while it’s narrow and V-shaped in males (typically < 90°).

- Greater Sciatic Notch: This notch is wide in females and narrow in males.

- Overall Shape: The female pelvic inlet is typically round or oval, while the male’s is heart-shaped.

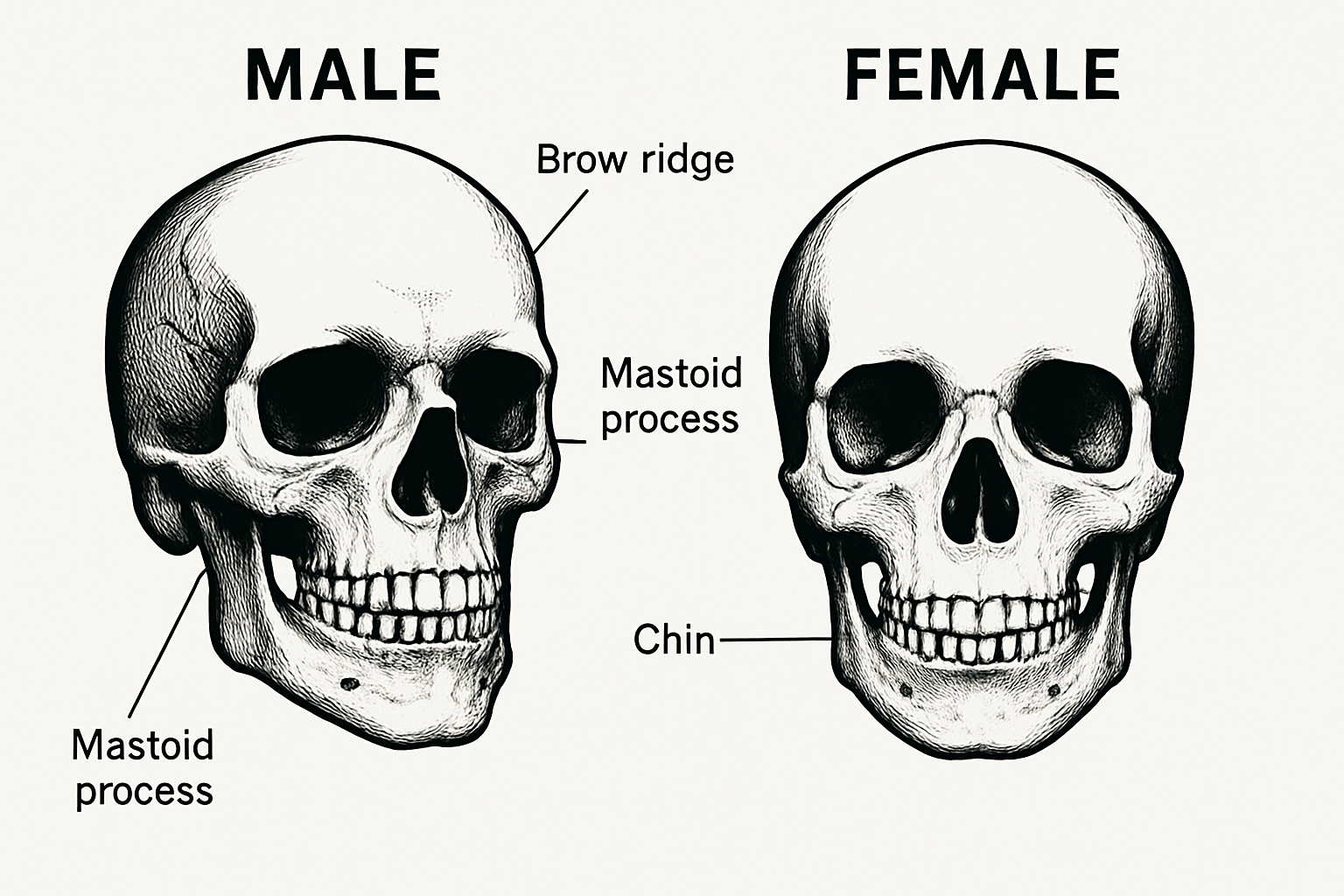

- The Skull: The skull is the second most reliable area for estimating sex. Male skulls are generally larger and more robust, with more prominent features related to larger muscle attachments. Key traits include:

- Brow Ridge (Supraorbital Ridge): More pronounced and bulging in males.

- Mastoid Process: A bony prominence behind the ear that is larger in males.

- Nuchal Crest: A ridge at the back of the skull where neck muscles attach, which is much more prominent in males.

- Chin (Mental Eminence): Tends to be square and broad in males, and more pointed in females.

Forensic Fact

While the adult pelvis is the best indicator of sex, the skeletons of children and pre-pubescent adolescents show very little sexual dimorphism. This makes it nearly impossible to accurately estimate the sex of non-adult skeletal remains based on morphology alone.

Further Readings:

- Scientific Working Group for Forensic Anthropology (SWGANTH):

- White, T. D., & Folkens, P. A. (2005). The Human Bone Manual. Academic Press. (A foundational textbook in osteology).