What is Forensic Pathology?

Forensic pathology stands as a critical subspecialty of medicine dedicated to determining the cause and manner of death in cases that are sudden, unexpected, suspicious, violent, or unexplained. It meticulously applies the principles and techniques of pathology – the study of disease and injury – to legal investigations. Unlike clinical pathology, which focuses on diagnosing disease in living patients to guide treatment, forensic pathology centers on the deceased, seeking to provide objective medical evidence

- What is Forensic Pathology?

- The Forensic Pathologist: A Medical Detective

- H2: The Autopsy (Post-Mortem Examination): A Detailed Look

- Purpose of the Forensic Autopsy

- The Autopsy Process: A Step-by-Step Examination

- Ancillary Studies & Specialized Techniques

- Special Considerations in Autopsies

- Determining Cause and Manner of Death

- The Importance of Forensic Pathology

- Ethical and Legal Considerations in Forensic Pathology

- Becoming a Forensic Pathologist: Education and Career Path

- Challenges and Future Directions in Forensic Pathology

- Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs):

The core mission of forensic pathology is, in essence, to “speak for the dead.” Forensic pathologists provide crucial answers that contribute not only to the administration of justice by identifying unlawful deaths and providing evidence for legal proceedings but also to public health by recognizing disease outbreaks, patterns of injury, and potential public safety hazards. Their work forms a vital bridge between medicine and law, offering clarity in situations often shrouded in uncertainty.

The Forensic Pathologist: A Medical Detective

A forensic pathologist is a highly trained physician who specializes in performing autopsies (post-mortem examinations) and interpreting their findings in a legal context. They are often described as “medical detectives,” using scientific methods to uncover the story behind a death.

Key Roles and Responsibilities

The responsibilities of a forensic pathologist are diverse and demanding:

- Performing Autopsies: This is a cornerstone of their work, involving a thorough external and internal examination of the deceased to document injuries and diseases.

- Crime Scene Investigation: In some jurisdictions, forensic pathologists may visit death scenes to gain firsthand understanding of the circumstances, observe the body in situ, and consult with law enforcement investigators. This practice varies depending on local systems (e.g., medical examiner vs. coroner systems).

- Evidence Collection and Preservation: During the autopsyAn autopsy, also known as a post-mortem examination or necropsy (when performed on animals), is a thorough and systematic medical procedure that involves the examination of a deceased person's body, typically to determine or confirm Read Full Definition, they meticulously collect and preserve biological samples (tissues, fluids) for toxicological, histological, microbiological, and DNA

DNA, or Deoxyribonucleic Acid, is the genetic material found in cells, composed of a double helix structure. It serves as the genetic blueprint for all living organisms. Read Full Definition analysis, as well as physical evidence found on or in the body (e.g., bullets, ligatures).

DNA, or Deoxyribonucleic Acid, is the genetic material found in cells, composed of a double helix structure. It serves as the genetic blueprint for all living organisms. Read Full Definition analysis, as well as physical evidence found on or in the body (e.g., bullets, ligatures). - Interpreting Injuries and Disease: They analyze the nature, extent, and patterns of injuries (e.g., gunshot wounds, stab wounds, blunt force trauma) and differentiate them from natural disease processes.

- Determining Cause and Manner of Death: Based on all available information, they establish the official cause (the specific injury or disease leading to death) and manner of death (natural, accidental, suicidal, homicidal, or undetermined).

- Providing Expert Testimony: Forensic pathologists are frequently called upon to testify in court (criminal and civil trials) to explain their findings and opinions to judges and juries.

- Consulting: They consult extensively with law enforcement agencies, prosecutors, defense attorneys, and families of the deceased, explaining complex medical findings in understandable terms.

Essential Skills and Qualities

To excel in this field, a forensic pathologist must possess:

- Profound Medical Expertise: A deep understanding of anatomy, physiology, disease processes, and injury patterns.

- Meticulous Attention to Detail: The ability to observe, document, and interpret even subtle findings.

- Objectivity and Impartiality: A commitment to unbiased scientific investigation, regardless of external pressures.

- Strong Ethical Grounding: Upholding the highest ethical standards in handling sensitive cases and information.

- Effective Communication Skills: The ability to clearly articulate complex medical information both in writing (autopsy reports) and verbally (court testimony, consultations).

- Resilience and Emotional Fortitude: The capacityThe amount of finished product that could be produced, either in one batch or over a defined period of time, and given a set list of variables. Read Full Definition to deal with disturbing and tragic circumstances on a regular basis.

H2: The Autopsy (Post-Mortem Examination): A Detailed Look

The forensic autopsy is a specialized surgical procedure performed by a forensic pathologist to gain a comprehensive understanding of a person’s death.

Purpose of the Forensic Autopsy

A forensic autopsy aims to:

- Identify the Deceased: If the identity is unknown, the autopsy can help gather information (dental records, DNA, fingerprintsFingerprint, impression made by the papillary ridges on the ends of the fingers and thumbs. Fingerprints afford an infallible means of personal identification, because the ridge arrangement on every finger of every human being is Read Full Definition, unique physical characteristics) for identification.

- Determine the Cause of DeathThe cause of death refers to the specific injury, disease, or underlying condition that directly leads to an individual's demise. It is a critical determination made by medical professionals, such as Medical Examiners or Coroners, Read Full Definition: To identify the specific injury, disease, or combination of factors that initiated the chain of events leading to death.

- Determine the Manner of Death: To classify the death as natural, accidental, suicidal, homicidal, or undetermined based on the circumstances and findings.

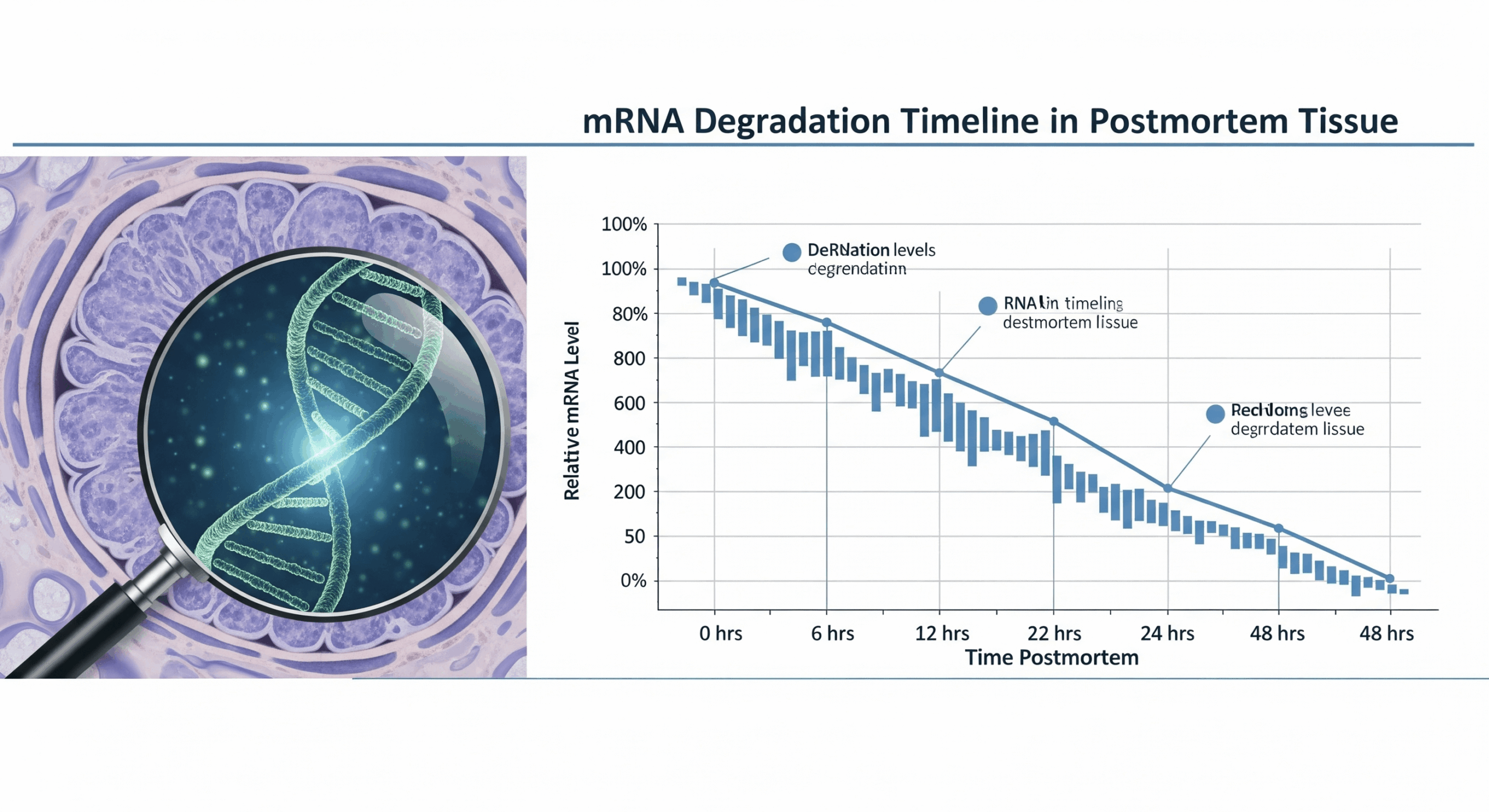

- Estimate Time of Death/Injury: While often challenging, pathologists assess postmortem changes and injury characteristics to provide an estimated timeframe.

- Collect and Document Evidence: To gather any physical or biological evidenceBiological evidence - physical evidence such as bodily fluids that originated from a human, plant or animal. Read Full Definition that may be relevant to a legal investigation.

- Document Injuries and Natural Diseases: To fully characterize all pathological findings, both related and unrelated to the cause of death.

The Autopsy Process: A Step-by-Step Examination

A forensic autopsy is a meticulous and systematic examination of a deceased individual.

- 1. Pre-Autopsy Investigation & Preparation: Before the autopsy begins, the forensic pathologist gathers extensive information. This includes:

- Scene Details: Reports from death investigators or law enforcement about where and how the body was found.

- Witness Accounts: Any available statements from individuals who may have seen the deceased or know about the circumstances.

- Medical History: Reviewing past medical records, hospital charts, and information from treating physicians can provide context about pre-existing conditions.

- External Examination of the Body Bag/Sheet: Noting any evidence or fluids present before the body is removed.

- 2. External Examination (The “Outside Story”): This is a critical, detailed visual inspection and documentation of the body’s exterior. The pathologist notes:

- General Characteristics: Apparent age, sex, race, height, weight, nutritional status, and any identifying features like scars, tattoos, or medical intervention marks (e.g., surgical scars, IV lines).

- Clothing and Personal Effects: If the body is clothed, these are carefully examined, described, and collected, often for further trace evidenceTrace evidence - Physical evidence that results from the transfer of small quantities of materials (e.g., hair, textile fibers, paint chips, glass fragments, gunshot residue particles). Read Full Definition analysis.

- Postmortem Changes: Documenting signs like rigor mortis (stiffening), livor mortis (settling of blood), and algor mortis (body cooling) to help estimate the postmortem intervalThe post-mortem interval (PMI) is the time that has elapsed since an individual's death. When the time of death is not known, the interval may be estimated, and so an estimated time of death is established. Read Full Definition.

- Evidence of Injury: Meticulous documentation of any trauma, including abrasions, contusions (bruises), lacerations, stab wounds, gunshot wounds, or burns. Each injury is described by its type, size, shape, location, and characteristics. Photographs and sometimes diagrams are made.

- Trace Evidence Collection: The body surface, hands, and nails may be swabbed or scraped for trace evidence such as hairs, fibers, gunshot residue, or foreign DNA.

- 3. Internal Examination (The “Inside Story”): Following the external exam, the internal organs are examined.

- Incisions: Typically, a “Y” or “U” shaped incision is made on the chest and abdomen, extending from the shoulders, down the midline of the chest, to the pubic bone. This allows access to the major organs of the chest and abdominal cavities. A separate incision may be made to examine the brain.

- Organ Examination in situ: Organs are first examined in their natural positions within the body cavities to observe relationships and any abnormalities like fluid collections or adhesions.

- Evisceration: The organs are then carefully removed, either individually or in a block (e.g., Rokitansky method).

- Dissection and Weighing: Each organ (heart, lungs, liver, kidneys, spleen, brain, etc.) is weighed, measured, and meticulously dissected. The pathologist looks for signs of injury, disease (e.g., tumors, infections, atherosclerosis), or congenital abnormalities.

- Sample Collection: Small samples of each organ and bodily fluids (blood, urine, vitreous humor from the eye, bile) are routinely collected for further ancillary studies.

- 4. Examination of the Brain: The scalp is incised, and the top of the skull is removed using a specialized saw. The brain is carefully removed, weighed, and examined for signs of trauma (hemorrhages, contusions), stroke, tumors, or degenerative diseases. It is often preserved in formalin for several weeks before detailed sectioning and microscopic examination, as fresh brain tissue is very soft.

- 5. Closure and Reinstatement of Organs: After the examination is complete, the organs (unless fully retained for specific reasons with proper authorization and according to jurisdictional policy) are typically placed back into the body cavity. The incisions are then sutured. The body is prepared for release to the family or funeral home, ensuring it is treated with dignity.

- 6. Reporting: The forensic pathologist compiles all findings from the scene investigation, medical history, external examination, internal examination, and ancillary studies into a comprehensive autopsy report. This legal document details the cause of death and other significant findings.

Ancillary Studies & Specialized Techniques

The gross findings at autopsy are often supplemented by various laboratory tests and specialized examinations:

- Histology: Microscopic examination of tissue samples taken from organs. This helps identify disease processes at a cellular level (e.g., inflammation, cancer cells, damage from ischemia) and can assist in dating injuries.

- Toxicology: Analysis of blood, urine, vitreous humor, bile, and tissue samples (e.g., liver, brain) to detect the presence and concentration of drugs (prescription, illicit, over-the-counter), alcohol, poisons, and other toxins.

- Microbiology: Culturing samples to identify bacteria, viruses, fungi, or parasites that may have caused or contributed to death (e.g., sepsis, meningitis).

- Radiology: X-rays are commonly used, especially in cases of suspected gunshot wounds (to locate projectiles), child abuse (to detect fractures of different ages), and some trauma cases. CT scans or MRIs (virtual autopsy techniques) are increasingly used where available.

- Forensic Anthropology: Consultation with a forensic anthropologist is crucial when dealing with skeletal remains to help determine age, sex, ancestry, stature, and identify signs of trauma or disease on bones.

- Forensic Odontology: Dental records are a primary means of identification. Forensic odontologists compare postmortem dental findings with antemortem records and can also analyze bite marks.

- DNA Analysis: DNA typing can be used for identification (comparing the deceased’s DNA with known samples or family references) or to link a suspect to the deceased via biological evidence. In cases involving decomposed or skeletal remains, advanced techniques like mtDNA sequencing from bone samples may be employed for identification when nuclear DNA is degraded, as mtDNA is more robust and present in higher copy numbers.

- Other Specialized Tests: Depending on the case, tests for genetic disorders, metabolic abnormalities, or specific chemical exposures may be performed.

Special Considerations in Autopsies

Certain types of death investigations require particular approaches:

- Pediatric/Infant Deaths: These are often complex and require specialized knowledge to differentiate natural diseases of infancy (like SIDS, once other causes are excluded) from accidental or inflicted trauma (child abuse).

- Deaths in Custody: Autopsies on individuals who die while in police custody or incarcerated are subject to heightened scrutiny to ensure transparency and identify any potential misconduct or neglect.

- Mass Disasters: Forensic pathologists play a key role in Disaster Victim Identification (DVI) efforts, performing autopsies to identify victims and determine causes of death.

- Exhumations: Court-ordered disinterment of a body for a repeat or initial autopsy may occur if new information arises suggesting the original cause or manner of death was incorrect.

Determining Cause and Manner of Death

Two of the most critical determinations made by a forensic pathologist are the cause and manner of death.

Cause of Death

The cause of death is the specific injury, disease, or combination thereof that initiates the unbroken chain of events leading to death. It is often stated in a sequence:

- Immediate Cause of Death: The final disease or complication directly resulting in death (e.g., pneumonia).

- Intermediate Cause(s) of Death: Condition(s) leading to the immediate cause (e.g., sepsis following a wound).

- Underlying (Proximate) Cause of Death: The disease or injury that started the lethal sequence of events (e.g., stab wound of abdomen, Alzheimer’s disease). This is the most important determination for vital statistics and public health purposes.

Examples include: gunshot wound to the head, coronary artery disease, blunt force head trauma, asphyxia due to strangulation, metastatic lung cancer.

Manner of Death

The manner of death explains how the cause of death arose. There are five recognized manners:

- Natural: Death resulting solely from a natural disease process (e.g., heart attack, stroke, cancer, complications of old age). This is the most common manner of death.

- Accidental: Death resulting from an unforeseen and unintentional event or chain of events (e.g., motor vehicle collision, fall, drowning, drug overdose where intent for self-harm is absent).

- Suicidal: Death resulting from an intentional, self-inflicted act committed with the intent to die (e.g., drug overdose with suicidal intent, self-inflicted gunshot wound, hanging). Evidence of intent is crucial.

- Homicidal: Death resulting from a volitional act committed by another person with the intent to cause fear, harm, or death, or through a reckless or grossly negligent act. It includes murder and manslaughter.

- Undetermined: This classification is used when, after a thorough investigation and autopsy, there is insufficient evidence to assign a specific manner of death. This may occur in cases with minimal information, advanced decomposition, or equivocal findings.

A temporary classification of “Pending” may be used while awaiting further studies, such as toxicology or histology results, before a final manner can be assigned.

The Importance of Forensic Pathology

The work of forensic pathologists extends far beyond the autopsy suite, having profound implications for various aspects of society:

- Criminal Justice:

- Identifying homicides that might otherwise be mistaken for natural or accidental deaths.

- Providing objective medical evidence crucial for prosecuting offenders or exonerating the innocent.

- Supporting or refuting accounts of events provided by witnesses or suspects.

- Helping to link suspects to crime scenes or victims through trace evidence.

- Public Health & Safety:

- Identifying communicable diseases (e.g., influenza, tuberculosis, emerging infections), triggering public health interventions.

- Recognizing patterns of injury that may indicate unsafe products, environmental hazards, or emerging drug abuse trends (e.g., opioid crisis).

- Providing data

Information in analog or digital form that can be transmitted or processed. Read Full Definition for injury prevention programs and public health policy.

Information in analog or digital form that can be transmitted or processed. Read Full Definition for injury prevention programs and public health policy.

- Civil Litigation:

- Findings are critical in insurance claims (e.g., accidental death benefits).

- Used in medical malpractice lawsuits to determine if substandard medical care contributed to death.

- Relevant in workers’ compensation cases.

- Closure for Families:

- Providing grieving families with accurate and understandable answers about why and how their loved one died, which can be crucial for the grieving process.

- Medical Advancement:

- Autopsies contribute to the broader understanding of disease processes, the effects of trauma, and the efficacy of medical treatments.

- Uncovering previously unrecognized diseases or new manifestations of known diseases.

Ethical and Legal Considerations in Forensic Pathology

Forensic pathology operates within a complex framework of ethical and legal principles:

- Consent for Autopsy: In most forensic cases (those falling under medical examiner or coroner jurisdiction), consent from the next-of-kin is not legally required for an autopsy, as it is mandated by law to investigate deaths affecting the public interest. This differs from hospital autopsies on patients who die of known natural diseases, where consent is paramount.

- Confidentiality and Privacy: Forensic pathologists handle highly sensitive personal and medical information, which must be protected according to legal and ethical standards (e.g., HIPAA in the US, though jurisdictional laws apply). Autopsy reports, however, are often public records in many jurisdictions.

- Handling of Human Remains: The deceased must be treated with respect, dignity, and care throughout the entire process, from transportation to the autopsy suite to release to the funeral home.

- Objectivity and Impartiality: Pathologists must conduct their investigations and form their opinions based solely on scientific evidence, free from biasThe difference between the expectation of the test results and an accepted reference value. Read Full Definition or influence from law enforcement, attorneys, or public opinion.

- Chain of CustodyChain of custody - The process used to maintain and document the chronological history of the evidence. Documents record the individual who collects the evidence and each person or agency that subsequently takes custody of Read Full Definition: Meticulous documentation and maintenance of the chain of custody for all evidence collected (biological samples, projectiles, clothing) is essential to ensure its admissibility in court.

- Courtroom Ethics: When testifying, the forensic pathologist has an ethical duty to present their findings truthfully and impartially, explaining complex medical concepts clearly to a lay audience.

Becoming a Forensic Pathologist: Education and Career Path

The journey to becoming a forensic pathologist is long and rigorous:

- Undergraduate Education: A bachelor’s degree with a strong emphasis on pre-medical sciences (biology, chemistry, physics, organic chemistry).

- Medical School: Completion of a four-year Doctor of Medicine (MD) or Doctor of Osteopathic Medicine (DO) degree.

- Pathology Residency: A 4 to 5-year residency program in Anatomic and Clinical Pathology (AP/CP) or Anatomic Pathology (AP) alone. This provides broad training in diagnosing disease through examination of tissues and bodily fluids.

- Forensic Pathology Fellowship: A 1 to 2-year specialized fellowship program focused exclusively on forensic pathology, including hands-on autopsy performance, scene investigation, forensic toxicology, and courtroom testimony.

- Board CertificationCertification is a process through which a scientist can demonstrate their knowledge and competence in a particular field or in performing specific assays. It involves meeting established standards and requirements set by a certifying body. Read Full Definition: After completing training, individuals must pass rigorous examinations administered by a certifying body (e.g., the American Board of Pathology in the United States) to become board-certified in Anatomic Pathology and then in Forensic Pathology.

- Licensure: A license to practice medicine in the state or region of employment is required.

Career Opportunities: Forensic pathologists work in various settings, including:

- Medical examiner’s offices (city, county, or state-level)

- Coroner’s offices (often working in conjunction with elected coroners)

- Hospital pathology departments (less common for primary forensic work)

- Academic institutions (teaching and research)

- Government and military positions

- Private consultation

Challenges and Future Directions in Forensic Pathology

Despite its critical importance, the field of forensic pathology faces several challenges and is continually evolving:

- Workload and Shortages: Many jurisdictions face a shortage of board-certified forensic pathologists, leading to heavy caseloads and potential delays.

- Funding and Resources: Adequate funding for facilities, staffing, technology, and training is essential but not always available.

- Advancements in Technology:

- Virtual Autopsy (Virtopsy): The use of CT and MRI scanning to create detailed 3D images of the body, which can supplement or, in limited cases, guide the traditional autopsy.

- Advanced Imaging Techniques: Enhanced methods for visualizing injuries and internal structures.

- Molecular Pathology and Genomics

- Standardization of Practices: Ongoing efforts to standardize protocols and reporting across different jurisdictions to ensure consistency and quality.

- Importance of Ongoing Research and Training: Continuous research is needed to better understand injury mechanisms, postmortem changes, and emerging diseases. Regular training keeps pathologists updated on new techniques and scientific advancements.

- Dealing with Mass Fatalities: Events like pandemics, natural disasters, or acts of terrorism place immense strain on forensic pathology services, highlighting the need for robust preparedness plans.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs):

Q1: What’s the difference between a coroner and medical examiner?

This varies by jurisdiction. A medical examiner is typically a physician, often a board-certified forensic pathologist, appointed to their position. A coroner is often an elected official who may or may not have medical training (though many employ physicians or forensic pathologists). Medical examiner systems generally rely more heavily on medical expertise for death investigation.

Q2: How long does an autopsy take?

A routine forensic autopsy typically takes 2-4 hours, but complex cases (e.g., multiple gunshot wounds, extensive decomposition, or cases requiring detailed dissections) can take much longer. This does not include the time for pre-autopsy review or post-autopsy report generation and ancillary testing.

Q3: Is the family charged for a forensic autopsy?

No. When an autopsy is legally mandated and performed under the jurisdiction of a medical examiner or coroner, there is no charge to the family.

Q4: Can a family refuse a forensic autopsy?

If the death falls under the legal jurisdiction of the medical examiner or coroner (e.g., it’s suspicious, unnatural, or a threat to public health), the autopsy is legally mandated, and the family generally cannot refuse it. However, authorities often work with families to address concerns where possible, especially regarding religious objections, though the legal mandate to investigate typically prevails.