Inconsistent Terminology in Forensics

A study published in the journal Biology has revealed inconsistencies in how forensic anthropologists use terms related to ancestry and race. The research recommends abandoning these outdated terms in favor of “population affinity,” a framework that better reflects the complexity of human variation shaped by historical and cultural events.

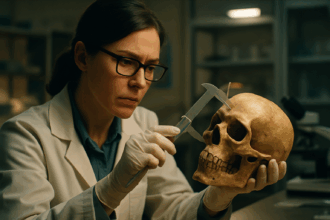

“Forensic anthropologyForensic anthropology is a special sub-field of physical anthropology (the study of human remains) that involves applying skeletal analysis and techniques in archaeology to solving criminal cases. Read Full Definition is a science, and we need to use terms consistently,” stated Ann Ross, the study’s lead author and a professor at North Carolina State University. “Our discipline’s reliance on traditional terms like race has led to confusion and potential misuse in practice.”

The Problem with ‘Ancestry’ and ‘Race’

Race, widely acknowledged as a social construct, often fails to align with skeletal evidence

In forensic anthropology, population affinity is proposed as a more precise"Precise" refers to the degree of closeness or consistency between multiple measurements or values taken under the same conditions. It indicates how well these measurements agree with each other, regardless of whether they are accurate Read Full Definition alternative. This concept evaluates skeletal characteristics based on historical and environmental influences rather than generalized racial categories.

Insights from the Study

The researchers conducted a comprehensive analysis, including:

- A review of papers from the Journal of Forensic Sciences (2009–2019), revealing widespread inconsistency in terminology.

- An examination of nine datasets encompassing 397 human remains from diverse regions, including Panama, Cuba, and Spain.

The findings challenge conventional classifications like “African,” “Asian,” or “European,” emphasizing that these labels oversimplify the nuanced realities of human variation. For instance, Panama’s diverse history—marked by indigenous populations, European colonizers, enslaved Africans, and Asian immigrants—renders such labels inadequate.

Reevaluating ‘Clines’ and Historical Context

The study also questions the concept of “clines,” which assumes geographically close populations are more similar than distant ones. Historical forces acting on neighboring regions, like Panama and Colombia, can result in vastly different skeletal characteristics, debunking this assumption.

Ross highlights that forensic anthropology must evolve to better understand how historical events have shaped modern skeletal populations. Focusing solely on historical populations limits the discipline’s ability to address contemporary challenges.

Addressing Structural Inequities

The study underscores the importance of reducing racism in forensic science

“This shift isn’t just about semantics,” Ross explained. “It’s about taking meaningful steps to reduce bias and structural inequities in our field while improving our scientific rigor.”

A Call to Action for Forensic Science

The findings advocate A person who aligns themselves with the patient, providing emotional support, referral services for follow-up, contact with social services, legal assistance, arrangements for transportation, presence in court, and for other needs. Read Full Definition for a reevaluation of forensic anthropology’s methodologies and vocabulary. Moving away from racial and ancestral categorizations, the discipline can align more closely with contemporary understandings of human diversity and historical context.

A person who aligns themselves with the patient, providing emotional support, referral services for follow-up, contact with social services, legal assistance, arrangements for transportation, presence in court, and for other needs. Read Full Definition for a reevaluation of forensic anthropology’s methodologies and vocabulary. Moving away from racial and ancestral categorizations, the discipline can align more closely with contemporary understandings of human diversity and historical context.

Journal Reference:

Ann H. Ross, Shanna E. Williams. Ancestry Studies in Forensic Anthropology: Back on the Frontier of Racism. Biology, 2021; 10 (7): 602 DOI: 10.3390/biology10070602